Last week, I was talking to the boys in the Lego Robotics team that I’m coaching, and they brought up the heartbreakingly sad story of the twelve year old child in Cleveland who was shot by police. My team – all good boys, ages 10-12 – were visibly shaken up by this. Especially the twelve year olds. They wanted to know what I knew, what details that had eluded them before. They wanted to understand. I hesitated for a moment. After all, these are not my children, and I have no idea how these topics are handled in their families. I know how we, in my family, talk about issues of racism and privilege and the duty of the individual to seek justice – which is to say frankly and clearly and in ways that they can understand – but these kids are under the care of other grownups. And so I hesitated.

And then one boy, also twelve (and he is a little thing – small arms, spindly legs, a mop of red hair exploding out of his head) said this, “Could this ever happen to me? I have toy guns. Will a police officer kill me too?”

And he looked at me. And he wanted me to tell him the truth. He needed me to tell him the truth. So I did.

“No, sweetheart,” I said. “That is not something that would happen to you. This is what white privilege means – you will never, ever in your life, have to face what that boy faced. Years of unfairness has made a situation in which some people privileged to be safe and some are not. You didn’t ask for it, but you need to understand it. It is your privilege to be angry, and it is your duty to be angry, too. That boy died because of racism, pure and simple. And it’s up to all of us to make the world more compassionate and sensible.”

And then we built robots out of Legos.

And I felt okay answering like that, because it is how I would answer my son, had he asked it (indeed, he was standing right there, listening intently), and it is how I would hope another adult would answer him as well.

It’s important to talk about the nature of privilege in a society that offers certain privileges to certain people and denies them to others. It is particularly important to talk about these things with children. Children care – and they care a lot – about fairness. About telling the truth. They care about justice and kindness and playing by the rules. When they are exposed to information – as they doubtless are right now – that is teaching them, right now, that some people are protected by law enforcement, and some simply are not, and we do not counteract that lesson with a “Yes, but….” or a “I know that’s unfair, but this is how we change it,” or a, “Good observation; now tell me why you think that is,” we are teaching our kids something very specific: that some topics are off-limits; that when wicked people come for your neighbors, it’s best to say nothing.

In my family, I choose a different path.

I talk about privilege with my kids. Their privilege. My privilege. My husband’s privilege. The aspects that are different and the aspects that are the same. I tell them that there the things that our culture makes easy for us are difficult for us to see. When we can understand the fact that roadblocks are set up for some and cleared away for others, we can use our collective voice and our relative freedom of movement to make things more fair for everyone.

When I talk about privilege, I also talk about what privilege is not. Privilege does not mean everything is easy and fancy-free and peeled grapes served on silver dishes and house elves that do all the washing. Privilege does not mean a lack of experience – though it does mean different experiences. Privilege does not mean racist – though certainly there are privileged people who are. Privilege is not a term of derision; it is simply a statement of fact.

And the fact is, my kids are privileged. Very much so. I mean, sure, their artisty parents sometimes struggle to pay the mortgage and we don’t have house cleaners or personal assistants or consistently working cars or whatever else rich people have in their houses and family situations. But they are white in a country that gives all kinds of free passes to white people, and they are the kids of an intact family unit in a country where that kind of thing matters more than it should, and they are the children of college educated parents who themselves are the children of college educated parents. And that makes a HUGE difference.

I talk about privilege not so that they have to apologize for their own experience – no one does. But rather, because I want to enlarge their understanding of the world around them so that they may better participate and know and love the whole human family. Privilege separates us. It insulates us from the pain of knowledge. It hides important facts, and alters our ability to analyze and understand even the most basic situations around us. It numbs us to the transformative power of empathy. And it prevents us from entering into true relationship with the larger human family.

(And, of course the Catholic in me sees another thing. We are many parts, but we are all one body. I am connected to you, and you, and you, and you, and you – bright beads on an endless string. You are my brother, my sister, my mother, my father, my child, and I am yours.)

The human person – regardless of where he or she falls in the cultural sphere – is in a state of constant change. To be human is to be in flux. We go from weakness to strength to weakness to strength to decay and dissolution. Our time on this planet is brief, and yet our expectations are enormous. When we recognize the humanity in another person – when we accept that humanity in a state of empathy and relationship and connection – when we choose to see the world as they see it and experience things as they experience – we enlarge ourselves. We enlarge our hearts. We enlarge our capacity for justice and kindness and goodness. We become that which has the potential heal the broken heart of the world.

When I talk to my kids about privilege, this is the lesson that I give them: “When someone points out your privilege to you – and believe me, this is going to happen a lot – there is only one proper, appropriate response: you say, ‘Thank you. Thank you so much.’ Because that person has just opened your eyes to a thing that had been hidden from you. That person trusted you enough to believe that you were a good and compassionate person and would understand. That person just opened a door for you to allow you to be a more complete member of the human family. That person just did you the hugest favor ever. Don’t blow it.”

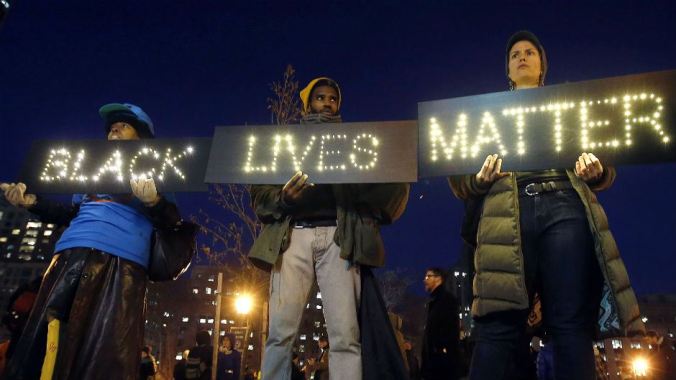

Racism exists. Privilege exists. Police brutality exists. Unfairness exists. Systemic bias exists. And these things cannot be fixed unless we talk about them. Name them. Create strategies to combat them. And sometimes take to the streets. Our great nation was founded, after all, by political protesters and those who engaged in civil disobedience. It is part of our DNA as Americans. And it gets things done. (This is another thing that I tell my kids.)

“The main thing,” I told them yesterday, as we looked through the photographs of the protests around the country, “is that evil persists in silent places. Evil loves fear and disconnection. Evil loves thoughtlessness and selfishness and despair. Hope isn’t just important: it’s subversive. Hope speaks truth to power. Hope listens. Hope finds common ground. Hope puts other people’s needs before our own. Hope is generous. Hope is spouse of Justice. Pray that they have lots of children.”

These are trying times to be a parent. And yet. I continue to have faith and I continue to hope and I continue to love. And I am teaching my kids to do the same.

“The ultimate tragedy is not the oppression and cruelty by the bad people but the silence over that by the good people.” — Martin Luther King, Jr.

I really like the way you explain privilege, especially because it applies not just to white privilege but to other kinds as well (such as gender, for example). I would only qualify it to say that terrible things do happen to the privileged as well. But certain kinds of terrible things are much less likely to happen to people with privilege, and what happened to Tamir is one of those things. The ex-Catholic in me is wary of ironclad absolutes :~) but also got his sense of human community from the same place it sounds like you do. Peace

Reblogged this on kebayoranlamadotcom and commented:

semetara 02195658308

Pingback: Sunday Salon: A Round-Up of Online Reading | the dirigible plum